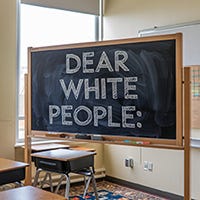

Dear White People,

Many of you either don’t or won’t understand the following aspects of institutionalized systemic racism, aspects that go far beyond individual prejudices. They are a deeply systemic issue that has been embedded in social structures and institutions, with historical power dynamics perpetuating the inequitable treatment of marginalized racial and ethnic groups to this day, often without conscious thought by individuals. The multifaceted effects of these dynamics continue to create disadvantages for these marginalized communities, prohibiting socioeconomic growth for many of their members.

Though racial and ethnic discrimination warrants far more coverage and discussion than can be put forth in an article of average size, this article is my attempt to cover in-depth the myriad of ways that racial bias in housing and neighborhood development practices has affected said communities, based upon what I’ve learned over the years from informal study.

Residential segregation has created profound disadvantages through systemic housing and neighborhood inequalities. Rooted in deliberate historical policies like Jim Crow laws, the Federal Housing Administration's discriminatory policies in the 1930s and 1940s encouraged white families to move to suburban areas while barring minorities, concentrating them in urban public housing projects with limited socioeconomic mobility.

Modern housing discrimination continues through subtler mechanisms, perpetuating historical patterns of segregation and inequality. While less overt than their historical counterparts, many of today's practices and policies remain purposefully effective in maintaining residential divisions along racial and ethnic lines, keeping minority groups in the shadows of their white counterparts.

Together, these modern mechanisms of housing discrimination work to maintain and even exacerbate the residential segregation established by historical policies, continuing to limit opportunities and perpetuate socioeconomic disparities for marginalized racial and ethnic groups, with devastating and multigenerational effects.

Exclusionary zoning laws play a significant role in this ongoing segregation. By mandating large lot sizes, restricting multi-family housing, or imposing other requirements, these laws effectively price out lower-income families, who are disproportionately minorities. This practice maintains the demographic composition of affluent, predominantly white neighborhoods. Biased lending practices continue to create barriers for minority homebuyers. Even when considering factors such as higher incomes and credit scores, studies show that minority applicants face higher rates of loan rejections, while those who are approved often receive less favorable terms, including higher interest rates, which increases the long-term cost of homeownership.

The strategic placement of public housing in already segregated, low-income areas further concentrates poverty and racial isolation. As a result, individuals and families in these communities often face systemic barriers that hinder upward mobility, including limited transportation options, inadequate educational systems, and poor social networks, all of which are crucial for socioeconomic advancement. Neighborhood disinvestment in minority-majority areas creates a cycle of declining property values and reduced opportunities. Banks may be less likely to approve loans for homes or businesses in these areas, while local governments may provide fewer resources for infrastructure and public services.

Real estate steering, where agents guide homebuyers to different neighborhoods based on race or ethnicity, remains a persistent problem. While illegal, this practice continues to shape neighborhood demographics and perpetuate segregation. Tactics such as "Crime-free housing ordinances" have emerged as a new tool for discrimination, allowing landlords to refuse rental to tenants with criminal records. This of course, disproportionately affects minorities due to the systemic biases they face in our corrupt criminal justice system.

Environmental injustice is particularly pronounced, with people of color disproportionately exposed to hazardous living conditions. They are more likely to live near oil and gas wells; experience higher air pollution levels; reside closer to toxic waste sites or on top of sites that were previously used for toxic materials; and suffer from inadequate and unsafe drinking water infrastructure. These environmental challenges directly and negatively impact the health and quality of life of all residents within such communities.

The economic effects of racism are equally severe. Homes in Black neighborhoods are systematically undervalued, averaging 23% less than comparable properties in predominantly white areas. During the 2008 financial crisis, foreclosure rates were 3.5 times higher in Black neighborhoods and 2.7 times higher in Latino neighborhoods. These practices and factors further erode opportunities for generational wealth-building and economic stability. Over 80% of low-income Black people and 75% of low-income Latino people are concentrated in federally defined "low-income" communities, compared to less than half of low-income white people. This concentration creates a cascading effect of disadvantage, forcing marginalized communities into environments with significantly reduced access to critical resources and socioeconomic opportunities.

Racial discrimination practices also have far-reaching effects on education, often confining minority students to underfunded and poorly resourced schools. Funding for public education in the United States is largely derived from local property taxes, which means that neighborhoods with lower property values - disproportionately those inhabited by racial and ethnic minorities - generate significantly less revenue for their schools. This systemic inequity leads to disparities in educational quality, where students in predominantly minority neighborhoods face overcrowded classrooms, outdated materials, and insufficient extracurricular programs.

Moreover, the historical legacy of redlining and exclusionary zoning laws has created attendance zones that mirror the segregated housing landscape, further entrenching educational inequities. As a result, minority students are often deprived of access to quality education that could provide them with the skills and opportunities necessary for upward mobility, thus perpetuating a cycle of poverty and limiting their potential prospects. The ramifications of this educational disadvantage are profound, affecting not only individual students but also the health and stability of their communities at large.

Employment opportunities and economic equality suffer from racial housing discrimination as well. Historically, biased practices in housing have restricted access to quality neighborhoods, which are often correlated with better job prospects and educational opportunities. For instance, the legacy of redlining and racially restrictive covenants has confined many Black families to areas with fewer job opportunities and inferior public services, including schools. As a result, individuals from these communities often face barriers when seeking employment, as they may lack access to reliable transportation or networks that facilitate job placements in more affluent areas.

This discrimination not only affects where individuals can live but also has profound implications for their economic stability and career advancement. For example, neighborhoods with high concentrations of poverty typically have fewer job openings and lower wages, which can hinder career growth. Additionally, even when individuals from marginalized communities obtain employment, they frequently encounter wage disparities compared to their white counterparts, despite having similar qualifications.

Racial housing discrimination extends also into healthcare access and quality of care. Housing conditions are a critical determinant of health, influencing everything from exposure to environmental hazards to access to healthcare services. Research indicates that individuals living in neighborhoods characterized by poverty and segregation - most often the result of discriminatory housing policies - face higher rates of chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular issues. For example, Black and Latino populations are disproportionately located in areas with high pollution levels, which correlates with increased respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

This systemic inequity in housing not only affects immediate living conditions but also limits access to essential health resources, creating barriers to timely and effective medical care. Moreover, the historical legacy of redlining and ongoing residential segregation significantly impacts healthcare outcomes. Communities that were once labeled as "hazardous" due to redlining practices continue to suffer from inadequate healthcare infrastructure. Studies show that residents in these areas experience worse health outcomes post-surgery compared to those in more affluent neighborhoods.

This highlights a stark correlation between neighborhood designation and health risks. Additionally, the lack of nearby healthcare facilities in predominantly minority neighborhoods often forces residents to rely on emergency services rather than preventative care, exacerbating health disparities. This reliance on emergency care is compounded by the fact that many healthcare providers in these communities are under-resourced, leading to poorer quality of care for patients. In addition, some non-hospital emergency clinics no longer work with Medicaid or Medicare, choosing to accept private insurance only.

As you can see, discriminatory practices in housing and neighborhood development affect far more than just housing and neighborhoods, reaching into every aspect of socioeconomics with disheartening severity. This is not conjecture, it’s not fake news. It’s not an excuse used by minorities to conceal shortcomings or failure to succeed.

It’s one of many sad, cold, hard truths, an ever-present skeleton in America’s closet that betrays the fact that though our nation is great when compared to many others, it is NOT the greatest as we’ve been led to believe. Nor will it be until equal rights, freedoms, opportunity, and financial stability are guaranteed for ALL regardless of racial or ethnic background.

In addition, despite the focus of this article being racial and ethnic discrimination, this country can not truly be considered great until equal rights, freedoms, opportunity, and financial stability are guaranteed for ALL CITIZENS, regardless of their background, sexual orientation, gender identity, religious belief or non-belief. UNTIL ALL ARE EQUAL, NONE ARE EQUAL.